This website uses cookies so that we can provide you with the best user experience possible. Cookie information is stored in your browser and performs functions such as recognising you when you return to our website and helping our team to understand which sections of the website you find most interesting and useful.

In the nineteen-fifties, local architecture was marked by the presence of the second-generation modern movement: abstract but adapted, open to the past but clearly not historicist, functional but neither mechanistic nor Existenzminimum.

Its leading protagonists were Coderch and Mitjans, who produced a wide range of basically residential buildings, especially in parts of the city expanding to the north, towards the mountain.

Many of these buildings have been points of reference for later generations and now form part of the local architectural DNA.

In the sixties, despite isolated cases of continuity of this trend (I am thinking of the works of Antonio Bonet Castellana, such as the dwellings on Carrer Consell de Cent or the Canòdrom greyhound track), there was a generalized stylistic and conceptual change in local architecture.

Influenced by the Italian trends of the time, from Neo-Liberty to historicism—in our country, in the form of a return to the Art Nouveau architecture (Modernisme) of the turn of the twentieth century—, brick, craftsmanship and detail once again came to the fore.

Aldo Rossi and Robert Venturi produced their influential theory at this time, heralding the future of this attitude: dissolving in the bottomless pit of Post-Modernism.

However, the sixties also raised other issues.

A liberation from custom and forms of behaviour (the hippie movement and American counterculture, for example) and, closer to home, a new breath of freedom that heralded the approaching end of Francoism.

London, the capital of emerging youth culture, became the new point of reference, not just for music and fashion, but also for architecture.

Archigram, the Independent Group and Reyner Banham, the most influential and far-sighted critic of his time, came onto the scene.

It was Reyner Banham who, in the hubbub of the British architecture of the moment, promoted New Brutalism as the central proposal of the time.

He took as his line of argumentation a sentence from Le Corbusier’s Vers une Architecture: “L’architecture, c’est avec des matières bruts, établir des rapports émouvants.”

Banham extended the argument to his contemporaries in the art world (Pollock, Jean Dubuffet and art brut) and architects such as the Smithsons, with his definition:

“What characterizes the New Brutalism in architecture and in painting is precisely its brutality, its je-m’en-foutisme, its bloody-mindedness.”1

Although local discussion focused on very varied issues, during these years Barcelona produced one of the best international examples of New Brutalism.

This was the Torre Colón, by the architects Anglada, Gelabert and Ribas (1965–1970).

La Torre, one of the city’s first skyscrapers, stands near the sea, beside the monument to Columbus, with the classicist Naval Command building as its plinth.

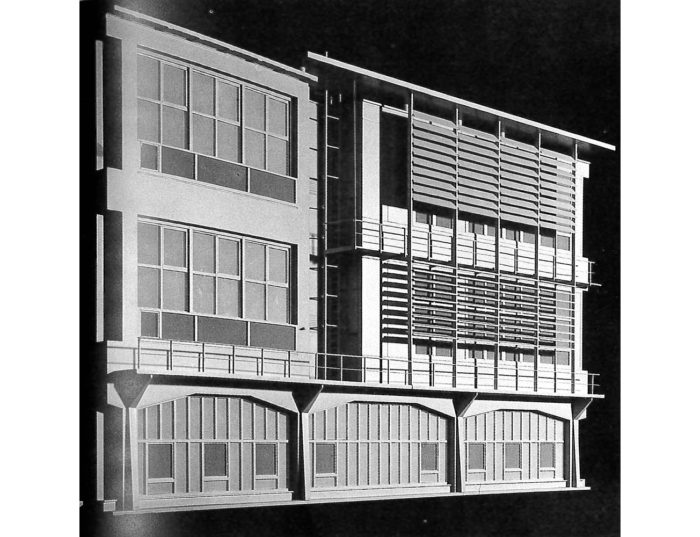

It has a tripartite order:

A large plinth that expands and articulates connection with its neighbours, a shaft with a slight distortion (actually constituting a quasi-hyperboloid) that, despite its hardness and weight, generates a certain instability and movement; and, finally, the crown on several floors, announcing the roof as a helipad before such a thing even existed.

Car parking on the lower floors of the volume, offices on the rest.

The surfaces of its envelope are hard, even its Mies-inspired curtain wall is heavy and stony. It is not lightness and transparency we are dealing with here.

The meeting with the street, with the urban human scale, had two moments of great interest. One, on the outside, sadly disappeared, with artistic interventions, was a pseudo-Chillida raw concrete portico and a pavement like the product of a volcanic eruption in front of the entrance.

The other memorable moment of the monster’s meeting with humans are the communal spaces on the ground floor.

The raw concrete is deployed with great intensity: in rough surfaces or on the stairs, whose steps seem to want to explode and fly outwards.

Reassessment of our Brutalist inheritance is a widespread contemporary phenomenon.2

In this case, recalling this work from the past is both a reference to the historical vitality of Barcelona’s architecture and highlights the many stimuli of our tradition.

Josep Lluís Mateo

1 “The New Brutalism”, The Architectural Review 118 and A Critic Writes. Essays by Reyner Banham, University of California, 1996. Also: Brutalismus in der Architektur. Ethik oder Ästhetik, Reyner Banham. Karl Kramer Verlag, 1966.

2 Among many other documents, see: SOS Brutalism: A Global Survey and Brutalism, various authors, Park Verlag, Zurich, 2012.

Text included in “Barcelona 60’s. Habitatge i Ciutat”. ETSAB, Barcelona, 2021